Have you seen the Questions feature on Facebook? Any Facebook user can post a question, such as: “What is the square root of 49?,” “What’s a good Nepalese restaurant in Russell Springs, Kentucky?” or “Why does it hurt when I pee?” and any user–that’s right, any user–can answer that question. Users then rate which answers they like the best, and they can also mark answers “unhelpful.” If an answer gets enough “unhelpful” marks, Facebook makes it quietly disappear.

Have you seen the Questions feature on Facebook? Any Facebook user can post a question, such as: “What is the square root of 49?,” “What’s a good Nepalese restaurant in Russell Springs, Kentucky?” or “Why does it hurt when I pee?” and any user–that’s right, any user–can answer that question. Users then rate which answers they like the best, and they can also mark answers “unhelpful.” If an answer gets enough “unhelpful” marks, Facebook makes it quietly disappear.

Seeing so many questions to which I know answers, I could not help but respond. Sadly, 3 of my answers have been marked “unhelpful” and have disappeared from the vox populi wisdom in Facebook questions. I have to disagree with that assessment, and so, for the sake of enlightening the unlearned masses, here are the original questions posed and my thoughtful answers to them:

Q. What happened before the Big Bang?

A. The Big Foreplay.

Q. What is it about cedar that repels insects?

A. All insects are anti-Semitic, and they especially detest Passover, let alone cedar.

Q. What are the best age-appropriate time travel novels for my nearly-13-year-old son?

A. If your son is 13 years old, by now he is grappling with his unresolved feelings of attraction for his mother. Why not let him resolve these conflicting emotions vicariously by giving him Time Enough for Love by Robert Heinlein, in which Lazarus Long, the main character, goes back in time and falls in love with his mother as a young woman.

Now why was that voted “unhelpful?” I read Time Enough for Love when I was a teenager, and look what a well-adjusted and productive member of society I turned out to be.

I admire Brian Cordry’s stealth approach to this last question with his recommendation:

You might try House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski. It’s a classic story of time travel, the good guy saving the girl, and other things that are relevant to a 13-year-old girl.

I voted this answer up, so it’s currently in 3rd place for the best recommendation. You may want to swing over to this Facebook question and vote it up in the hopes that the parent asking this question won’t actually bother trying to read the book, and some 13-year-old son will have his mom or dad knock on his bedroom door, hand him House of Leaves, and say cheerfully, “Here, son, here’s a great time travel novel!”

Update: Yikes! I had the wrong link for the time travel novel question. I fixed it. Go and vote up House of Leaves for best age-appropriate time travel novel!

My further adventures with Facebook Questions and the tragic conclusion are continued in this post.

Another review I never completed. Too bad, because I really gave Jacques Loussier what for. So here are my observations on that dead horse beater, from a La Jolla Summerfest concert, Aug. 22, 2008. My colleague Kris Eitland did a dance review of the same concert, which you may find here.

“…music, finished as no music is ever finished. Displace one note, and there would be diminishment. Displace one phrase, and the structure would fall.”—Peter Shaffer, Amadeus

Thus spake the character of Antonio Salieri on the compositions of Mozart, a sentiment shared by many music lovers, myself included. Only a jackass or a genius would be foolhardy enough to tinker with Mozart’s musical perfection.

Jacques Loussier is no genius.

Exactly what Loussier is, besides incredibly lucky to sustain a career long after his 15 minutes were over in the 1960s, is unclear. Plenty of teenage classical pianists have better technique and expressive abilities than Loussier. Sophomores in college jazz programs can knock off a better solo than Loussier can after nearly a five-decade-long career. The guy cannot swing, and his harmonizations are thoroughly uninspired.

Nevertheless, a major choreographer such as Pascal Rioult felt something when he heard Loussier’s version of Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 23 in A major, K. 488. Maybe it was pity. No matter what Rioult perceived in this music to inspire him to devote his creative time and energy, and the talents of 8 dancers, not to mention the thousands of dollars to pay for the costumes and lighting, Rioult was unable to make a choreographic silk purse out of this musical sow’s ear. How this landed on a class act like SummerFest is also unclear. You don’t sell a pig ear in Nordstroms; it belongs with all the other pig ears in a self-serve bin at Petco.

In Loussier’s disfigurement of one of the most sublime piano concertos ever written, walking bass lines intrude on classical sections for no discernable reason, other than to wink at listeners who think a walking bass line popping up in a classical work is cute. The mournful Adagio is trivialized by transforming it into a slow, square waltz. Loussier’s drummer imposes a splang-splang-a-lang ride on the cymbal over Mozart’s music, although it’s not so much of a ride for Mozart as it is a hit-and-run. Mozart’s notes and phrases were displaced by Loussier, with the unsatisfactory results Antonio Salieri expected. I’m not sure hearing the piece as a recording was an improvement over a live performance, although, as a corollary, I was certainly happy to see that no SummerFest musicians were psychologically damaged by having to play Loussier’s artless arrangement in concert.

Using classical compositions as a basis for a jazz arrangement is an extremely difficult feat to pull off. Many have tried, few have succeeded—Ellington’s Nutcracker Suite and Miles Davis’s solos over Gil Evans’s re-interpretations of Falla and Rodrigo come to mind as musical victories. The rest of jazz history is littered with stillborn Songs of India and Dvorak Humoresques, perhaps popular for a week or two, and then promptly and justly forgotten.

There are jazz musicians today who have found working with classical materials extremely fruitful. Why not invite Uri Caine or Matthias Rüegg to SummerFest? San Diego’s own Anthony Davis, while not exactly dipping into the 19th-century classical European tradition, nevertheless has forged a unique vocabulary that deftly inhabits the cracks between classical music and jazz. Any of these gentlemen have more talent in the last phalanx of their fifth toe than Loussier possesses in his entire being.

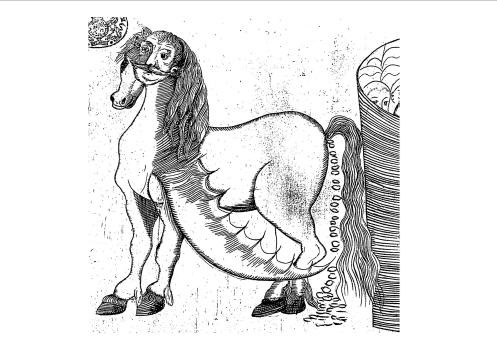

or A relation, shewing how they were first bred, and descended from a horse-turd, which was enclosed in a butter-box. Together with a most exact descripton of that great, huge, large, horrible, terrible, hideous, fearful, … prodigious, preposterous horse that shit the same turd; who had two faces on one head, the one somwhat resembling the face of a man, the other the face of a horse, the rest of his body was like the body of an horse, saving that on his shoulders he had two great fish finns like the finns of whales, but far more large: he lived somtime on land, but most in water; his dyet was fish, roots, … A very dreadful accident befel him, the fear hereof set him into such a fit of shiting, that he died thereof: … Also how the Germans following the directions of a conjurer, made a very great box, and smeared the in-side with butter, and how it was filled with the dung which the said monstrous horse shit: out of which dung within nine days space sprung forth men, women, and children; the off-spring whereof are yet alive to this day, and now commonly known by the name of Dutchmen; as this following relation will plainly manifest

This is quite possibly my favoritest broadsheet ever printed: a fine example of ethnic-bashing in 17th-century England.

To see a PDF of the complete broadsheet, click here

Although Percy Grainger lived most of his life in the U.S., he established his own museum in Melbourne, Australia.

Although Percy Grainger lived most of his life in the U.S., he established his own museum in Melbourne, Australia.

After Grainger had passed away, one day his widow came into the Grainger Museum. She was grimy, coated with dirt as if she’d been outdoors for a week, and hauled a gunny sack along side of her. She walked up to the Museum Director’s office and hoisted the sack up onto his desk with a big clatter, throwing off clouds of dust.

“What’s this?” the director asked her.

“It’s Percy’s bones,” she replied. “He wanted them to be made into a wind chime and hung outside the Museum.”

The director, squirming uncomfortably, asked Mrs. Grainger, “How did you get his bones?”

“I took him out to the desert,” she said, “and let him be picked clean and let his bones bleach in the sun.”

The Museum Director politely refused to accept Grainger’s remains, explained that making such a wind chime would be against the law, and that she needed to give him a proper burial. The Director later discovered that Grainger had stipulated in his will that his bones be made into wind chimes for the Museum, and Percy’s widow was complying with her late husband’s wishes.

–as told to me by Australian composer/pianist/conductor Keith Humble

Accepting his Natural Endowment of the Parts Award

Yesterday, I received the stunning news that I was selected to attend the NEA Arts Journalism Institute in Classical Music and Opera at Columbia University’s School of Journalism in October. As one who:

- never took a single journalism class in college;

- never held a full-time journalism job;

- writes exclusively online these days at www.sandiego.com (the last professional thing of mine to be published on processed wood pulp was a San Diego Union-Tribune review in 1995);

- spent over a decade as a composer applying for grants and to competitions without winning a single thing; and

- had straight A’s in high school except for one class, Expository Writing

I am alternately shocked, ecstatic, giddy, and bewildered. I am experiencing something that I have never really had in my life before: major professional validation, and it’s an odd feeling–but I’m adjusting.

The Institute is a 10-day, intensive workshop (nearly all expenses paid!) where I will be expected to write reviews overnight (I haven’t done that in over 15 years), attend performances at the Metropolitan Opera and New York Symphony (where fellows will meet the superstar of European modernism, Finnish composer Magnus Lindberg), and contribute to a collaborative blog written by attendees. In preparation for this, I need to buy a laptop with wifi and nice new clothes (I don’t think my usual polo shirt, jeans, and sneakers will cut it in Manhattan).

If you’d like to read the work of mine that convinced the Institute to shower me with your tax dollars, I am posting links below. In the meantime, I will enjoy the very atypical feeling of glory I am wondrously experiencing.

CSI Beethoven–Inside Ludwig’s Head, by Orchestra Nova: Forensics, Fidelio, and the Fourth

La Jolla Symphony: American Accents: Wu Man is a Dish For the Gods

In describing the agony of child birth to me, an inexperienced man, a female acquaintance of mine once said that it was “like trying to shit a watermelon.”

That’s about what it felt like for me to write this review, but now it’s over and done with, and I’m a proud daddy.

Read about the American premiere of Bright Sheng’s Northern Lights, and the world premiere of Anthony Newman’s Sonata Populare, as well as old music by dead white European dudes.

Eric Lyon

Blog visitors appear to be coming here for Eric Lyon, so here’s a review of a chamber orchestra work of his, Splatter. You have to dig down a few paragraphs, but I think I captured the spirit of Lyon’s work. A few months after writing this review, I was studying the Tippett Piano Concerto, and what do you know? There’s a duet for timpani and celesta there, but Tippett’s sincerity and atmospheric use of the instruments is completely different from Lyon’s hilarious juxtaposition (reminiscent of the trombone/contrabass duet in Stravinsky’s Pulcinella, where the trombone blows away the contrabass). Will someone–ICE, London Sinfonietta, Boston Modern Orchestra Project–please record Splatter?

This review originally ran in the La Jolla Light Nov. 28, 1991, with the completely unintriguing headline of “Seriousness and satire make for a satisfying musical month.”

I’d like to share with you a bit of the musical cornucopia I enjoyed over the last two weeks. In the spirit of Thanksgiving, I’ll skip over the bad parts and give praise where it is due.

On Nov. 8 I attended a performance by Les Ballets Africains, a company of more than 30 dancers and musicians from Guinea sponsored by the San Diego Foundation for Performing Arts. The exoticism of the music, dances, and costumes was fascinating enough; in combination with both the dancers’ and the musicians’ unflagging energy, the evening was tremendously stimulating. This was some of the most exuberant dancing I’ve seen all year. And how often do you get to see more than 30 people loudly playing percussion instruments in complex, interlocking patterns?

Lukas Foss made his first appearance with the San Diego Symphony that weekend as well. On Saturday, Nov. 9, he conducted his own Fanfare for Orchestra; it was not the sort of jubilant, up-tempo piece one might infer from the title. Rather, it consisted of long melodic lines in the strings punctuated by raucous staccato bursts from the piano, percussion, winds, and brass. Foss’s long string melodies spun out effortlessly; he came of age at a time when it seemed that just about every big American composer was striving to successfully compose what Copland called “the long line.” Fanfare struck me as earnest, unpretentious, and effective.

A performance of Copland’s Third Symphony followed; written in 1946, when the idea of the “Great American Symphony” was in the air, this piece is one of the best contenders for the title. Copland’s non-balletic scores have been unjustly neglected in American concert halls; it was refreshing to hear live a work I had only know before from a single recording (Copland’s own with the London Philharmonic). While there were technical glitches (most noticeably faulty intonation among the first violins during their highest passagework), the proper emotions and drama were there; it was a stirring performance of a noble piece.

On Wednesday, Nov. 13, I heard three exceptional pieces expertly performed by SONOR at UCSD. Two of these works were by young composers, David Lang (b. 1957) and Eric Lyon (b. 1962), and both of them were marked by an immediate, aggressive physicality coupled with a wry (perhaps even cynical) detachment in the manipulation of their frequently dark and violent musical materials.

Lang’s Dance/Drop was written for baritone saxophone, bassoon (both amplified), piano, synthesizer, and percussion. The first movement was dominated by harshly repeated chords, accompanied by loud, repetitious percussion writing (for brake drum and thunder sheet, kick drum, tomtoms); the harmonic/melodic rhythm, despite the driving pulses, was sneakily unpredictable. The second movement was characterized by a long, quasi-modal melody played by the bari sax, bassoon, and synthesizer; a brooding texture was created by simultaneously overlapping adjacent notes in this slow melody with these instrument. Dance/Drop is sinister, but with a hip attitude—there’s a real sense of fun, even of burlesque, to the work.

Lyon’s Splatter, the audience favorite of the night, has a sense of fun as well, but at the expense of self-righteous avant-garde music written since 1940. Scored for a small orchestra of 23 players (solidly conducted by John Fonville), Splatter mercilessly skewers those composer who write uncompromisingly difficult pieces (for both performers and listeners) by accurately pastiching such music; Splatter subverts the listener’s expectation by either abandoning this material and moving off to something completely different, by pushing the material to ludicrous extremes (such as—I kid you not—a duet for timpani and celesta), or by treating this complex material as just another chunk of music in a sampler to be audaciously looped or played back at inappropriate moments. Splatter is inspired devilment which roguishly insults music that many of Lyon’s UCSD colleagues aspire to compose; it is sheer genius on Lyon’s part that his lunatic musical rhetoric is so convincing. Eric Lyon is at the crest (along with David Lang) of a new wave of American music that is the most innovative, refreshing movement to come along since Minimalism.

While Lang’s and Lyon’s works may have caused all the hubbub at this SONOR concert, a stinging performance of Ralph Shapey’s De Profundis showed that some of the old-timers could be just as violent and abrasive as these young punks. De Profundis, a contrabass concerto written for Bertam Turetzky in 1960 (and who brilliantly performed this intesnse work, with John Fonville conducting), was unrelenting in its angst, a hyper-Expressionistic lament from “out of the depths.” Let’s hope that this marked the beginning of more performances of Shapey’s distinctively powerful music in San Diego.

On Nov. 15 Yoav Talmi led the San Diego Symphony in a crisp, tightly-performed rendition of Mozart’s Piano concerto no. 15 with soloist Peter Frankl. Frankl interpreted Mozart in a Romantic vein, bringing a somewhat heavier tone than we expect in a Mozart concerto to his playing, augmented with a good helping of rubato. However, it was ultimately a persuasive performance.

Talmi then conducted Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony from memory. The orchestra sounded superb; the different sections were flawlessly coordinated in their playing, and the entire orchestra was extremely responsive to Talmi’s phrasing and dynamic shaping. Peronsally, I find this symphony a puzzle; but for audience members who love Bruckner, this was unquestionably a performance to cherish.

Maria Bachmann

On Saturday, Nov. 16, violinist Maria Bachmann and pianist Jon Klibonoff presented a recital at Sherwood Auditorium. Their performance of Beethoven’s C minor Sonata was beyond reproach, and their rendition of Brahms’s D minor Sonata was equally compelling. Bachmann is clearly a musician with a great future ahead of her, and her dedication to chamber music is heartening, as is her dedication to contemporary composers. The two presented the local premiere of Clockwork by Sebastian Currier (b. 1959), a handsome piece with its stylistic feet firmly planted in the middle of the contemporary American compositional mainstream.

Christopher Rouse, "The Stephen King of Classical Music"

I’m looking forward to hearing the Calder Quartet play Christopher Rouse’s Third Quartet at Summerfest on Friday Aug. 20. (I’m reviewing that concert for http://www.sandiego.com) Rouse describes his new string quartet:

My overall description of the piece would be something akin to a schizophrenic having a grand mal seizure. This, at least, was the image to which I continually referred as I composed the music. The twenty-minute score is dedicated to the Calder Quartet and, after a slow introduction, follows a standard fast-slow-fast ordering of sections played without pause. The music is staggeringly difficult to play, and I believe this to be my most challenging and uncompromising work to date.

Until this formidable-sounding work is unleashed on San Diegans, here’s an unfinished, unpublished review of mine and some links to full performances to whet your appetite. It’s from the last time Rouse’s music was heard at Summerfest (Aug. 2008). He’s hit or miss in my book, but when he connects, he knocks it out of the ballpark, as he did two years ago:

As a freshman composition major at the University of Michigan School of Music, convinced of my inviolate destiny to make a living writing classical music, there was one figure there particularly inspiring to me. He was a 30-year-old composer with a special postdoctoral fellowship, and it seemed that this fellowship paid him to do little more than compose music and hear it performed at U of M.

Fellowships in academia for creative people are not that unusual. What made this composer so special was that the performers at the School of Music—not just students, but faculty as well—actively pursued this composer to write them music or to give them an earlier work to perform. In 1980, performance faculty—not only at Michigan, but also in most colleges and universities–did not take an active part in soliciting new works, let alone in performing them. A tenured composer could have an office adjacent to a tenured performer, and Said Performer would not play, or even demonstrate an interest in, Said Composer’s music.

So here was this composition fellow—he wasn’t even really faculty, although he did teach a course there titled “Messiaen, Ali Akbar Khan, and Jefferson Airplane”—upon whose office door everyone knocked for commissions and scores, and there was good reason for this. Whenever this composer had a work on a concert, his music completely blew away whatever else had the misfortune to occupy the same page of the program. I had previously encountered this phenomenon of overwhelming the musical competition with only two other modern composers: Varese and Crumb (both of whom were influences on this composer—in fact, he even studied with the latter). It was obvious to anyone at U of M that through the School of Music halls strode a Major Talent, and I wanted so much to have the career that he had when I turned 30.

In the last year of his residency at U of M, the University Symphony Orchestra asked him to write a brief work that they could use to open their concerts during their upcoming European tour. That work, a violent, grinding, quirky overture called The Infernal Machine, ultimately became the breakthrough piece for Christopher Rouse.

Nearly three decades later, Rouse is one of the most successful American composers of his generation, if success is measured by commissions and live performances. On Friday night, SummerFest presented two golden oldies by Rouse, a pair of percussion ensemble works he wrote while still in his twenties: Ku-Ka-Ilimoku and Ogoun Badagris. Just as Rouse’s music did when I was an undergraduate at University of Michigan, these two rock-‘em-sock-‘em compositional juggernauts obliterated the competition for the evening. Their force and immediacy has not diminished over the years.

Influenced by Polynesian drumming (Ku-Ka-Ilimoku) and Haitian drumming (Ogoun Badagris), both works are similar in their relentless rhythms and gleeful aggression; but beneath their undeniable momentum lie shifting rhythmic cross-currents and skillful orchestrations. Both works also reveal a mastery of timing: Rouse knows just how long to repeat a pattern or texture before altering it or moving on to something else, and the heart-pounding climaxes in retrospect seem inevitable.

The UCSD percussion ensemble, red fish blue fish, usually performs more radical works: the shock and awe of Xenakis, the wacky wonders of Cage, the spacy grandeur of John Luther Adams, or the minimalist reductionism of Reich. Their rendition of Rouse, a composer previously unperformed by them, was more restrained in both loudness and tempo than other percussion groups, but their moderation allowed for more nuance than usual, and also demonstrated that there is more to Rouse’s musical language than velocity and volume. Leader Steven Schick played percussion parts for each work, guiding red fish blue fish from within to performances of Rouse that were—well, rousing. (Watch their performance here)

I was initially skeptical of hearing both Rouse pieces back to back—despite different meters and instrumentation, they’re a little too much of the same thing. As it turned out, it took a while after the end of Ku-ka-Ilimoku to set up for Ogoun Badagris, an interval that was amusingly filled by the theatrical shenanigans of Fabio Oliveira, who humorously improvised on the cuica while dancing goofily center stage. It was an inspired bit of pantomime that broke up the boredom, and put a little (and much-needed) emotional space between each percussion work. His hijinks inadvertently carried over into the arresting introduction of Ogoun Badagris—the brief cuica solo there induced chuckles through the hall. No one laughed, however, once Rouse’s brutal musical depiction of human sacrifice got underway.

I love classical music, but one of the things I hate most about classical music concerts is that most venues do not allow you to take your drink into the hall. Granted, most symphony halls are posh venues, and I don’t blame management for not wanting to have to clean up beer and wine spills in their lovely halls.

But it sure would be wonderful to hear a Mahler symphony with a glass of fine wine in your hand. (This movement in particular. And I always thought this one sounded like a beer drinking song from a Rathskeller.) However, even if you could bring your drink in–would you really want to?

My experience with most classy venues is they serve terrible wine. OK, I understand they want to maximize their profits. But couldn’t they get a discount from a winemaker in exchange for some program space or even a placard at the bar?

Fortunately, the best place in town to have dinner while seeing a show–Anthology–has started a classical music program. There are still some kinks to be worked out, but the series has promise. You can read my review here. Mrs. Hertzog laughed loudly and frequently at this one, so I think you’ll enjoy it!

My friend Melissa complained about a stranger stopping his car near her house and dashing out to take a whiz in the woods, said stranger unaware that:

1) Soon a house will be built on that lot

2) She had a full view of his pit stop

I was inspired to write this brief little parody describing her predicament. Feel free to contribute extra stanzas in the comments section!