Admit it–you’ve always wanted to see Richard Wagner and Giuseppe Verdi go mano a mano in a fight to the death. But who would win?

I posed this very question in the LA Weekly, and the results are in. But you’ll have to click here to read the analysis.

Now, let’s get rrrrrrrrrrready to collect rrrrrrrrrrroyalties!

First edition cover of The Case Against Tomorrow by Frederik Pohl

The Case Against Tomorrow

by Frederik Pohl

Ballantine Books, 1957

Excerpt from “The Midas Plague”

Blessed are the poor, for they shall inherit the Earth.

Blessed Morey, heir to more worldly goods than he could possibly consume.

Morey Fry, steeped in grinding poverty, had never gone hungry a day in his life, never lacked for anything his heart could desire in the way of food, or clothing, or a place to sleep. In Morey’s world, no one lacked for these things; no one could.

Malthus was right–for a civilization without machines, automatic factories, hydroponics and food synthesis, nuclear breeder plants, ocean-mining for metals and minerals…

And a vastly increasing supply of labor…

And architecture that rose high in the air and dug deep in the ground and floated far out on the water on piers and pontoons…architecture that could be poured one day and lived in the next…

And robots.

Above all, robots…robots to burrow and haul and smelt and fabricate, to build and farm and weave and sew.

Frederik Pohl was among a group of writers in the 1950s who moved American science fiction away from space opera, realistic attempts at future prediction, and stories that asked “What if?” using logical extrapolation. As his contemporaries William Tenn, Robert Sheckley, and Cyril Kornbluth all did, Pohl used science fiction to hold up a satirical mirror to his world, finding sympathetic publishers in magazines such as Galaxy Science Fiction and The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

While the contents of The Case Against Tomorrow may have had some bite in the 1950s, it’s dated rather poorly. Stories such as ‘The Census Takers,” “The Celebrated No-Hit Inning,” “Wapshot’s Demon,” “My Lady Green Sleeves,” and “The Candle Lighter” are entertaining enough for a mindless read, but there’s not much that stays with you. The one exception in this book is “The Midas Plague,” one of Pohl’s most anthologized stories.

In “The Midas Plague,” Pohl envisions a reversal of American consumption and status after World War II. There are so many consumer items produced by automated manufacturing that every citizen is obliged to buy as many items as they can. The more prestigious one is, the less one has to consume. Conversely, a young husband starting out in an entry-level corporate job has to live in an enormous mansion with his wife, drive several cars, and buy more clothes and goods and food than they can possibly consume. In that society, one is not permitted to waste things–say, wear a suit once and then throw it away. No, it has to go through its useful life and show wear before it can be recycled to produce new consumer products. Everyone struggles to keep up with their neighbors by having as little or less than them.

Morey Fry, the protagonist of the story, finds a way to consume more goods so they move up the social ladder and get to consume less. The reversal of 1950s corporate ladder climbing and the pursuit of affluence is still very funny, but it’s sad to realize what a land of plenty the U.S. was during that time–enough so that a reader could imagine a society of unbridled consumerism for its lowliest citizens.

Recommendation: You can read “The Midas Plague” elsewhere; skip this collection and pick up one of Pohl’s collaborations with Cyril Kornbluth such as The Space Merchants or Search the Sky instead for cynical, wry 1950s science fiction. If you’re looking for satirical short stories from that decade, just about any short story collection by Kornbluth (without Pohl), Sheckley, Tenn, or Damon Knight beats these tales.

Hardcase

by Dan Simmons

St. Martin’s Press, 2001

Opening:

Late one Tuesday afternoon, Joe Kurtz rapped on Eddie Falco’s apartment door.

“Who’s there?” Eddie called from just the other side of the door.

Kurtz stood away from the door and said something in an agitated but unintelligible mumble.

“What?” called Eddie. “I said who the fuck’s there?”

Kurtz made the same urgent mumbling noises.

“Shit,” said Eddie and undid the police lock, a pistol in his right hand, opening the door a crack but keeping it chained.

Kurtz kicked the door in, ripping the chain lock out of the wood, and kept moving, shoving Eddie Falco deeper into the room…

Five pages later, Kurtz has choked Falco, broken his nose, mangled his hand in a garbage disposal, and thrown him out a sixth-floor window.

The violence and the pace continue similarly for 43 more chapters. Dan Simmons’s prose is wonderfully taut and economical. Every word is well-chosen, so the novel focuses on dialogue and plot. The character of Joe Kurtz is brutal, borderline amoral, smart, and extremely competent.

The great-granddaddy of this type of novel is probably Fast One by Paul Cain, a hard-boiled novel sadly forgotten now except by fans of the genre. In the more immediate past, the obvious predecessor to Kurtz is Richard Stark’s character, Parker. (Simmons even dedicated Hardcase to Richard Stark).

Kurtz is a private investigator who has lost his license by Chapter 2. As he points out to his faithful female assistant, Arlene, you don’t need a license to do investigations. Soon he is working for a mobster, trying to find a missing accountant.

The violence in Hardcase is horrific, but believable, unlike the cartoon action of Mickey Spillane’s Mike Hammer. The story never falters; Simmons weaves several complicated plot lines together which culminate in a satisfying ending.

Recommendation: Ultraviolence, action, an intelligent protagonist who outwits enemies, thrills, and prose that does its job by staying out of your way so you focus on the plot and characters–what’s not to like? If you were grabbed by the opening page quoted above, you’ll want to read this book.

Another Visual Bookshelf summary/review that I wrote before the site disappeared

Meet The Residents: America’s Most Eccentric Band!

By Ian Shirley

188 p., SAF Publishing, Wembley, UK, 1998

Is it possible to write an accurate biography about a group of performers who have woven a thick shroud of obscurity around them? Perhaps not. As one of the Residents wrote to their unauthorized biographer Ian Shirley, “You must know that everyone you spoke with intentionally lied to you at some point.” However, until another biography of The Residents comes out, this book will have to do.

Since this is the only lengthy treatment of this mysterious band, Shirley’s book is a must-read for any Residents fan. Shirley discusses their roots (they are supposedly from Shreveport), their early meeting with Phillip “Snakefinger” Lithman, their move to San Francisco, and the mysterious (and likely fictitious) N. Senada. Each of their projects, up to The Gingerbread Man and Bad Day on the Midway, is described as well.

Shirley contends that The Residents are not trained musicians. When they need someone with some chops, the Residents bring talented musicians into the studio or take them on the road. It is possible that some of the founding members of The Cryptic Corporation are actually Residents, including Homer Flynn, John Kennedy (who bankrolled their projects), Hardy Fox, and/or Jay Clem.

Some interesting celebrities have crossed The Residents’ path, notably Penn Gillette, who served as a “one man Greek chorus and…a comedian” for the concert version of the Mole Show in 1982. (You can hear him doing the announcements on Mark of the Mole.) Matt Groening wrote The Official W.E.I.R.D. Book of The Residents in the late 1970s (W.E.I.R.D. was the Resident’s fan club, standing for: We Endorse Immediate Resident Deification).

The book includes discussions of their aborted film project, Vileness Fats (since restored and released on the Icky Flix DVD), their early music “videos” (actually short films), their CD-ROMs, and their concert tours. In the back of the book you will find a decent discography.

Residents fans will love this. Readers with little knowledge of their work may be intrigued enough to want to listen to a CD, or just confused (especially if they’re not familiar with more experimental types of pop music).

I wrote a brief overview of The Residents, their importance to popular music, and a detailed review of their Talking Light tour from 2010, which you may read here.

Sex and opera go together like condoms and KY. Scheming to remove another’s clothes and post-coital complications are the lubricants that enable operatic plots to thrust forward.

But could Louis Andriessen be taking things a little too far in his new opera, Anais Nin? Read my preview at the LA Weekly and decide for yourself.

Update: Listen to a preconcert talk with Louis Andriessen and Reinbert de Leeux here.

A forlorn glimpse at a career which is no longer possible in the United States

Rivethead: Tales from the Assembly Line

Ben Hamper

If you ever saw Roger and Me, you’ll probably remember Ben Hamper. He’s the depressed guy who was laid off from General Motors, turned on the radio, heard “Wouldn’t It Be Nice?” by the Beach Boys, and broke down crying. Rivethead is the tale of Ben’s life working for General Motors.

Hamper grew up the son of a son of a Flint auto shop rat, and wound up one himself. Along the way, he encountered Michael Moore, at that time editor of the alternative newspaper Flint Voice (which became the Michigan Voice). Moore persuaded Hamper to contribute articles to his paper, most of which chronicled his adventures working for General Motors on the assembly line. Moore eventually wound up at Mother Jones (where he didn’t last long), but he took Hamper with him (in print anyway). Hamper became a celebrity, the blue collar columnist celebrated in the Wall Street Journal and Esquire.

This is a hilarious yet sad book. In some ways, it’s a mill-worker’s version of MASH: men breaking rules and goofing off to alleviate the boredom. Drinking on the job, “doubling up” on shifts (one guy covers for two, so the other can disappear for a few hours), playing “rivet hockey”–all are described in the book. Hamper keeps getting laid off and rehired, eventually suffering a mental breakdown from the strain of being unemployed. A true slacker, Hamper is a master at getting paid for doing as little work as he can.

One of the funniest episodes in the book describes the creation of a GM mascot to boost workers’ morale, the GM Quality Cat. Some guy in a giant cat suit walked around the plant in a misguided attempt to inspire workers. There is a contest to come up with a name for him (Wanda Kwit, Roger’s Pussy, and Tuna Meowt are some of the losing entries). The grand winner is: Howie Makem. Here’s Ben’s description:

“Howie Makem stood five feet nine. He had light brown fur, long synthetic whiskers and a head the size of a Datsun. He wore a long red cap emblazoned with the letter Q for Quality. A very magical cat, Howie walked everywhere on his hind paws. Cruelly, Howie was not entrusted with a dick.

Howie would make the rounds poking his floppy whiskers in and out of each department. A ‘Howie sighting’ was always cause for great fanfare. The workers would scream and holler and jump up and down on their workbenches whenever Howie drifted by. Howie Makem may have begun as just another Company ploy to prod the tired legions, but most of us ran with the joke and soon Howie evolved into a crazy phenomenon.”

This book gives you a good taste of how mind‑numbing assembly work is, and it’s an excellent look at how the workers really felt inside one of America’s great corporations.

Michael Moore has set up a web page in praise of Rivethead and provides some generous excerpts as well here.

John Cage (b. Sept. 5, 1912; d. Aug. 12, 1992)

Lots of John Cage events coming up in L.A. this year, in honor of Cage’s centennial.

Some observations about Cage and his compositions over at sequenza21.

A list of Cage-related events on the horizon in my recent story for the LA Weekly.

"Life is one big minefield, and the only place that isn't a minefield is the place they make the mines."--Michael O'Donoghue

I wrote a few detailed book reviews for the now defunct web site/app Visual Bookshelf. I have fairly eclectic reading tastes, and I tend to enjoy whatever everyone else ignores, and so, as a favor to the authors who have provided me with many wonderful hours, as well as Bloghead visitors looking for something different to read, I’m re-publishing some of my best reviews on this site.

Michael O’Donoghue was one of the most influential comedians of the 1970s. As one of the founding members of National Lampoon and as a head writer for the first few seasons of Saturday Night Live, O’Donoghue developed a take-no-prisoners style of comedy in which any subject matter–the Holocaust, Vietnam atrocities, hot-off-the-press murders (as you can see, he was obsessed with death)–could be used as a basis for comedy. He pushed the limits of comedy, taking material that was extremely disturbing and putting a comic spin on it.

O’Donoghue started out in the early 60’s as an avant-garde theater producer/director/actor in Rochester, NY (he dropped out of U of Rochester), including the satirical The Death of JFK produced in early 1964. A manuscript of one of his Rochester plays, the automation of caprice, attracted the attention of Evergreen Review editors with its sex, torture, random violence, bestiality, and drug-induced hallucinations. O’Donoghue moved to New York, and soon became a regular contributor to Evergreen Review.

The comic strip he created for them, The Adventures of Phoebe Zeitgeist, became one of Evergreen Review’s most popular features. Illustrated by Frank Springer in a straight comic book style, no one had ever seen an absurd, sadistic strip like Phoebe Zeitgeist. It is certainly one of the earliest underground comics.

O’Donoghue wound up at National Lampoon, and helped shape the magazine’s groundbreaking humor. He co-wrote and produced National Lampoon’s first comedy album, Radio Dinner, and took charge of the National Lampoon Radio Hour, re-invigorating an essentially dead genre.

Viewers of Saturday Night Live may remember his character, Mr. Mike. Mr. Mike’s funniest skit (to this teenage viewer at the time) was his impersonation of Mike Douglas:

He enlisted Buck Henry to introduce him as “the king of impressionists.” After Henry’s introduction, big band music, worthy of the cheesiest variety fare, blares as O’Donoghue runs onstage. Dressed in a Vegas-style tuxedo, he snaps his fingers and smiles to the audience in “sincere” showbiz fashion.

“Thank you, thank you very very much, ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to…you know, when you’re in show business it seems you always end up at some bar at 4 o’clock in the morning arguing over who’s the best singer, who’s the best dancer, who’s the funniest comedian. But I think there’s one thing everybody agrees on and that’s who’s the nicest guy in show business and of course I’m talking about Mr. Mike Douglas…

Having recently watched Mike’s show, the “king” had a funny thought: What if someone took steel needles–say, 15, 18 inches long, with real sharp points–and plunged them into Mike’s eyes? What would his reaction be? O’Donoghue removes his glasses, turns his back to get into character, grabs his face, and screams and thrashes across the stage. At first the image seems ridiculous, but O’Donoghue pushes it and acts as though he is in serious physical pain. Audience members who line the stage watch O’Donoghue in amazement. A few laugh; the rest seem horrified and confused by the man who writhes and kicks just inches from their faces. Finally, O’Donoghue spills off the end of the stage, but his screams continue to fill the studio. Buck Henry walks on applauding. “Uncanny, isn’t it?,” he says.

After writing/directing his NBC special, Mr. Mike’s Mondo Video (which the network refused to air without cuts, so he found a movie distributor), O’Donoghue became a hot Hollywood commodity. But his refusal to dilute his vision and/or accommodate genuinely sincere collaborators resulted in a series of unfinished/unproduced screenplays, and numerous pitch sessions in Hollywood which never resulted in any green lights.

In 1981, he was called back to help resuscitate Saturday Night Live, which had gone down the tubes following Lorne Michaels’ departure. O’Donoghue was made head writer, and he hired his idol Terry Southern to work on the show. As before, his more controversial sketches never aired (including a sketch where an SS officer informs a demanding American private that the Germans had a good excuse for the Holocaust, whispering it in his ear and the ear of a concentration camp survivor and a Russian soldier–we never learn what the excuse is, because a dog runs across the stage with the script in his mouth, and Neil Simon can’t catch it). However, O’Donoghue was responsible for a live violent punk act (Fear) with skinheads in the audience and for having William Burroughs read excerpts from Naked Lunch.

O’Donoghue was known for his elaborately staged parties, and in his early New York years, for his surreally decorated loft. He had a series of ultimately unsatisfactory relationships (except for perhaps his last wife, Cheryl Hardwick, the keyboard player from SNL). This book does a good job recapturing the highs and lows of his career.

Here are some of my favorite O’Donoghue quotes from the book (and you can find more here):

- “A lot of my humor is like Christ coming down from the cross–it has no meaning until much later on.”

- “I don’t think television will ever be perfected until the viewer can press a button and cause whoever is on the screen’s head to explode.”

- “Better a daughter in a cathouse than a son writing screenplays. She’ll suck a lot less dick.”

- “Making people laugh is the lowest form of comedy.”

"Ja! Gustavo Dudamel ist Der Dude."

Over at my new publisher, the LA Weekly–my take on Gustavo Dudamel’s Mahler Project, an amazing endeavor involving 2 orchestras, 11 vocalists, and 16 choirs. The Dude played all 9 symphonies from memory, in the span of 3 weeks, an unprecedented accomplishment–and I was at every program. Read all about it here and here.

Now if I can only remove those damned Mahler earworms from my brain….

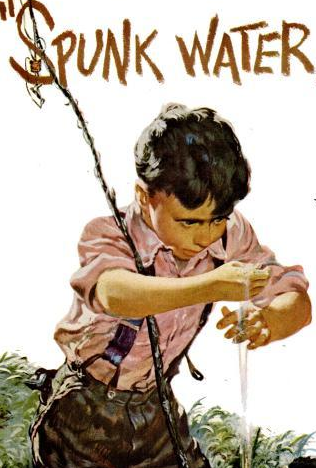

Life was much simpler in the early 20th century, when boys were satisfied with the simple pleasures of being alone outdoors. An ad in Life magazine recalls those halcyon days when a carefree lad could go out into the woods by himself and make spunk water.

From Life Magazine, Aug. 8, 1949, p. 98

Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg: towering geniuses of classical music, pitted against each other by critics and professors as the two great rivals of the early 20th-century. But take away Arnold’s filter-tips and Igor’s pince-nez, toss them in a metal cage, and let’s see who’s the last man standing—the dour Austrian professor who emancipated dissonance, or the tiny Russian conductor who boosted other composer’s musical styles like a kleptomaniac stealing ketchup packets.

Read the full article at the LA Weekly to find out who wins!